Audio reading of this section (English)

One of, maybe the most important factors in even determining who was a Senogalatis was based on what language they spoke. Obviously, that was Senogalaticos (Gaulish). Senogalaticos simply means “Ancient Gaulish”. This language shares its ancestry with several other related languages. The roots of it lie in a language known today as Proto-Indo-European. There is of course no way nor record of what speakers of that language referred to it. It dates back to the Tritaisson Artuates (“Third Age of Sone” or Neolithic) and is thought to have been spoken in the Eurasian steppes, roughly western Russia and eastern Ukraine, extending south to the Caucasus region. There it resided until the Cauologâ (Yamnaya) peoples of the Early Bronze Age began to migrate and expand, bringing it out into the world. Of course, Proto-Indo-European had predecessors as well. For the sake of preserving reasonable brevity however, we will start at this point in time. This language from this location spread off in mainly two directions: southeastward into what is now Turkey and Iran, eventually making its way down to northern India, and westward further into Europe. Thus how the language was named. At various times and places, the language evolved enough distinctions to be considered a different language by scholars. It is at that stage we witness the development of the ancestral languages of many of the “branches” of Indo-European languages. Examples are Proto-Indo-Iranian, Proto-Tocharian, Proto-Greek, Proto-Balto-Slavic, Proto-Italic, and yes, Senocelticos (Proto-Celtic) – the ancestor of Senogalaticos.

Senocelticos likely arose in the Ulumagos (Urnfield) period. The culmination of the evolution from Proto-Indo-European spoken at its western extent. It is the ancestor of all Celtic languages. The living descendants continue to be spoken to this day: Welsh, Irish, Scots Gaelic, Breton, Cornish, and Manx. The latter two having been revived after a period of disuse. Notable ancient descendants include Lepontic, Celtiberian, and Senogalaticos (Gaulish). Senogalaticos emerged as a language in the first century AAC, roughly 6th century BCE. It lasted for around 1,000 years. Noric, which was spoken in the old Isarnoberios (Hallstatt) heartland, and Galatian, which was spoken in central Anatolia were either very closely related or other dialects of Senogalaticos (especially Galatian). Thus the range of this language was from southern Britain to north central Turkey. Mirroring of course, the Senogalatîs themselves. A staggering distance for a people that were not a centralized polity!

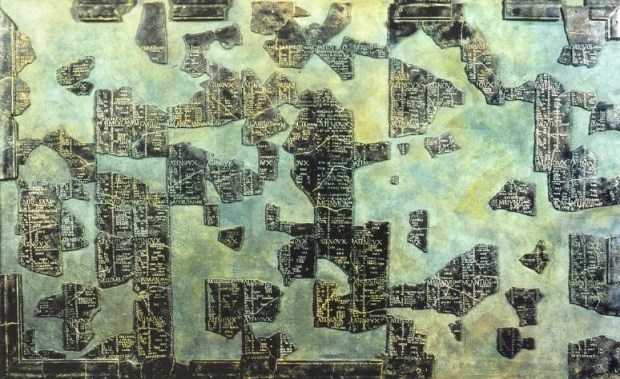

One of the largest records of Senogalaticos is actually this calendar, the Coligny Calendar.

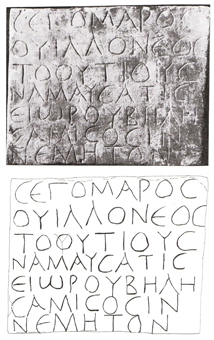

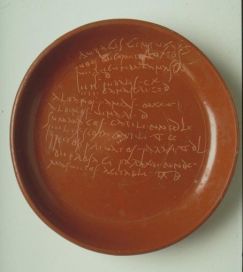

It is of course obvious that they spoke. But how did they write? The Senogalatîs to our knowledge didn’t invent a writing system. Assuredly if we ever find that they did, we at Bessus Nouiogalation will utilize it at lightspeed! There are three scripts that we’re aware of that they used throughout time. The first was a North Italic script that the Etruscans used, the Lepontoi (Lepontic) peoples, closely related to the Senogalatîs, utilized this script (evidenced in the alphabet of Lugano). In turn the Senogalatîs in northern Italy used it as well. Secondly, thanks to trade with the Greeks and due to their presence as neighbors in Massalia, many older inscriptions made by the Senogalatîs utilised ancient Greek script. Lastly, but certainly not least, interaction with and later subjugation by the Romans led to the usage of Latin script. The last of these is from which the majority of inscriptions are found. All said, we don’t know how much they’d write because they didn’t, to our knowledge, leave behind books like their Mediterranean counterparts. It is also said that the Druides discouraged the use of writing, with the belief that it weakened memory. With the advent of the smartphone, we remember less and less phone numbers, so perhaps they had a point. As their order was great in power and influence, it is perhaps in part due to that that we see less Senogalaticos writing. They certainly did write, however.

The following images are courtesy of Mnamon: Ancient Writing Systems in the Mediterranean. Credits.

This is a Gallo-Etruscan inscription from Briona.

This is an example of a Gallo-Greek inscription. From Vaison-La-Romaine.

A Gallo-Latin inscription from La Graufesenque.

In the end, Senogalaticos was replaced by Vulgar Latin in some places, and Germanic languages in others. This took the course of about 4-500 years following the end of Senogalaticos independence. Thus, it didn’t go down easily or without resistance. The model within which it was replaced was a common one. The death of the language likely wasn’t intentional, it didn’t have to be. Simply enough, after independence the language of the nobility, government, and trade changed over time. Latin became the “prestige language” and knowledge of it was necessary for social advancement. It was adopted by the wealthier classes first, for whom though they were bilingual for a long time, gradually shifted to more and more Latin. This would eventually reach the common people and at that point the Latin they spoke would eventually evolve into Old French. A few hundred words from the language survived into French, and as French speakers conquered England via the Normans, some of those words also made it into English. Such as ambassador from ambactos, car from carros, and budget from boudicos. About 1000 attested words are known of and more are being discovered to this day. Attempts are made to revive the language in different ways and forms for different purposes. Including of course Bessus Nouiogalation’s attempts.

More reading about the language of the Senogalatîs:

- Gaulish: Language, Writing, Epigraphy by Alex Mullen and Coline Ruiz Darasse

- On the position of Gaulish within Celtic

- from the point of view of glottochronology by Václav Blažek

- Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise by Xavier Delamarre

- Les Noms Gaulois by Xavier Delamarre

- La Langue Gauloise by Pierre Yves-Lambert

- Gaulish Inscriptions by Wolfgang Meid

- Le Gaulois par les exemples by Gerard Poitrenaud