Audio reading of this section (English)

Around 220 SA-130 AAC (according to our calendar) or roughly 800-450 BCE we enter the period of the Isarnoberios (“iron bearer” – in academia, Hallstatt) culture. The start of this period was characterised by finds of iron weapons, which demonstrated that the metal was in the ascendant. Though at the earlier stages, bronze was still more common and iron was being worked like bronze. It took a length of time before they would figure out ironworking for its own sake.

Trade with the Mediterranean world had far reaching significance. It is thought that elite status had much to do with control of the flow of goods from the south. Imported goods are often found in graves from this age. One of the most famous being that of the Vix Krater, found in a grave of a wealthy (probably royal) woman.

The famous Vix Krater. [Wikimedia Commons]

The most common occupation of people by this point in history was certainly farming. Spelt, barley, emmer wheat, lentils, broad beans, peas (grains and legumes) are known to have been cultivated. Along with flax, camelina, and other plants for making fabric, flavouring food, and medicine. Pigs, cattle, sheep, and goats provided most of the meat. Transhumance (the following of herds though their cycle of pastures throughout the year was still practised in some cases, but sedentary farming was more common. Hunting at this time was not yet the proclivity of mostly elites, and regardless, fish was widely available.

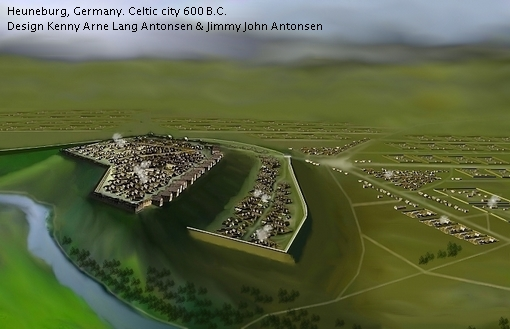

Salt mining, while it certainly existed in previous ages, was quite prolific by this time. This would have led to other occupations such as folks who would cure meats to preserve them. Metalworking was quite advanced when compared to their contemporaries. Tools and sacred items being common finds with quality craftsmanship. With the development of large fortified sites like Heuneburg (numbered around 5000 people) proto-urbanisation was already starting to happen.

A fine example of Isarnoberios (Hallstatt) artwork, the Strettweg Cult Wagon. [Wikimedia Commons]

An artistic reconstruction of the proto-city at Heuneburg. [Designed by Kenny Arne, Lang Antonsen, and Jimmy John Antonsen]

In the western areas of this culture (from which is the main part in which the Senogalatîs emerged) iron swords were common in princely and warrior graves. In the east, it was mostly daggers. Tools, pottery (though decreasingly over time), jewellery, belts, and other clothes accompanied people who were by this point as much buried as cremated in the west, where the east held on more to cremation as their own ancestors did. Spindle whorls and items related to textile work are also found. Much of the precursor to the Senogalatîs is found in this culture. Very rarely, statues are also found. Such as one called the “Warrior of Hirschlanden”.

The Warrior of Hirschlanden. [Wikimedia Commons]

The Mediterranean world certainly had an influence on this culture, but it was by no means a copy of it. When ideas and art styles arrived from the south it did not take long for the Isarnoberios (Hallstatt) peoples to reinterpret motifs in the context of their local cultures. As can also be seen with Etruscan influence on their arts. The importing of wine became common due to this exchange.

Other than wine, beer was produced locally and was a widely consumed drink. Products made of beeswax were also very common according to the analysis of pottery at Mont Lassois (a major early Iron Age excavation site in France) often containing it. Toward the end of this age, however, this society entering the age of iron started to change rapidly, and the old structures started to collapse. It is in this period of decline that we see the emergence of the Senogalatîs.

Further reading on the Isarnoberios (Hallstatt) Culture:

- The Human Body in Early Iron Age Central Europe, by Katharina Rebay-Salisbury (who so kindly and freely shares this entire book)

- Local elites globalized in death: a practice approach to Early Iron Age Hallstatt C/D chieftains’ burials in northwest Europe, by David Fonijin and Sasja van der Vaart-Verschoof

- New insights into Early Celtic consumption practices: Organic residue analyses of local and imported pottery from Vix-Mont Lassois, by Maxime Rageot, Angela Mötsch, Birgit Schorer, David Bardel, Alexandra Winkler, Federica Sacchetti, Bruno Chaume, Philippe Della Casa, Stephen Buckley, Sara Cafisso, Janine Fries-Knoblach, Dirk Krausse, Thomas Hoppe, Philipp Stockhammer, and Cynthianne Spiter