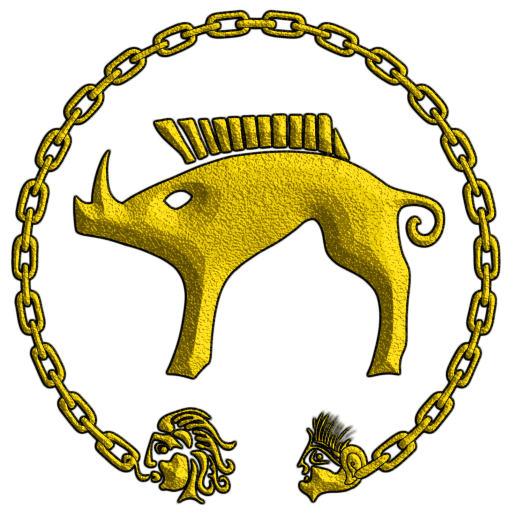

Canecouepoi, Canecomatreiâ: Geniâ Galatês

Behind every legend, there is a glimmer of truth. And with every hero’s journey, there is always a beginning.

The debate had been going on ever since midday and it showed no sign of reaching a conclusion.

On one side, there was the chieftain of the village, a man by the name of Bretanos. His daughter, Celtina, stood at his side listening patiently. On the other side, there stood a group of warriors, the strongest and bravest of the tribe. Or so they had boasted when they’d first been summoned to this meeting.

But their bravery seemed to have disappeared as soon as the chieftain brought up why he had called them together.

Bretanos’ offer was simple.

“Go to Garanos and bring back my cattle that he stole from me,” Bretanos had told them. “In return, you will receive enough land and gold to start your own tribe.”

The reward was more than generous. But the response from the warriors had been the same unyielding reply.

“Garanos has the strength of three warriors. He has already killed a number of our warriors as if they were nothing more than annoying gnats buzzing around his head.”

Despite the truth of their words, Bretanos had reminded them why the herd of cattle was so important. “Those cattle are vital to the survival of our tribe, especially with winter approaching.”

Celtina, the daughter of Bretanos, interrupted them. “In addition to what my father offers, I will give my hand in marriage to the one who brings our cattle back.”

Many of the men of the tribe had been seeking to marry Celtina. Not only was she the daughter of the chieftain, but she was also the most beautiful woman in the neighboring lands. Yet Celtina had refused all of the suitors.

But even with her offer now, still the warriors answered with a firm no.

During the exchange between Bretanos and his warriors, the old man had been sitting unnoticed in the shadows as he listened intently to the debate.

Finally, he stood up. “I will go,” he said in a deep voice as he leaned upon his walking stick for support.

All eyes turned to regard the man who had just made the offer, examining him closely.

He was old, definitely past the prime age for a warrior – past the prime age for any occupation for that matter. His white beard fell down to his chest, apparently compensating for the few hairs fighting to remain on his bald head. His arms and fingers were as gnarled as the branches of an ancient oak tree. His skin was as dark as tanned leather.

But despite his fragile and ancient appearance, he strode forward and spoke in a powerful voice. “I will go and bring back your cattle,” he said to Bretanos.

The chieftain stared at the old man for a moment with a look of disbelief mixed with sympathy.

“I appreciate your kind and generous offer,” Bretanos finally said, “but I don’t think you are a match for the likes of Garanos.” He paused before continuing as if searching his memory. “I don’t believe I have ever seen you before. What is your name?”

“My name is Ogmios,” the old man answered, “and I come from a place far away from here. Despite the way I appear, I will lead your cattle back to you along with this thief Garanos for you to punish as you deem fitting.”

Without another word, Ogmios turned and left.

“I do not think the old man will succeed,” Bretanos said to his daughter. “But even if he does bring back the cattle, I would never expect you to marry him.”

Celtina stared at her father in shock. “I will not be the reason for shame and dishonor to fall upon my father’s name.”

“But I cannot allow a man three times your age -“

“Nor will I allow you to go back on your word,” Celtina interjected.

It had been four days since Ogmios had left to go take back the stolen cattle. Many believed that the old man had been killed, though they secretly hoped that senility had made him lose his way on the journey to where Garanos lived. At least that way, the old fool would still be alive.

Celtina sat down beside her father and took his hand. “I fully understand the reasons why you don’t want me to marry Ogmios if he does return.” She leaned in closer, making sure her father was listening. “It was my idea to offer my hand in marriage to the warrior who would return the stolen cattle, and I knew full well that it could possibly be someone I would find less desirable and may not choose to marry under normal circumstances. But I will not break my word nor will I allow you to do so either.”

“Proud and headstrong,” Bretanos said as he shook his head.

Celtina laughed. “Qualities I thankfully received from my father.”

Their conversation was interrupted by people yelling outside, their voices growing louder and louder.

As they stood up to go and see what was going on, a warrior entered. “My lord, you had better come and have a look.”

Bretanos and Celtina stepped outside and glanced in the direction from where the commotion was coming.

It was Ogmios returning, leaning upon his walking stick.

To their surprise, though, he was not alone.

Behind him, there slowly followed the largest warrior any of them had ever seen. Garanos. In a pasture nearby, the stolen herd of about fifty cattle were grazing.

As Ogmios got closer, they noticed that his lips were moving as he stared down at the ground in front of him.

“The old man is mumbling to himself,” Bretanos said.

“I don’t think so,” Celtina said. “Look closer.”

Bretanos looked again. At first, he thought he was imagining what he was seeing but he soon realized his eyes were not deceiving him.

Ogmios was speaking to Garanos, who was listening so intently that his head was cocked to the side so that he would not miss a word. He even stumbled every few steps because he was paying more attention to the old man’s words rather than where he was walking.

“It looks as if the old man is pulling Garanos behind him with a chain,” Bretanos said to his daughter.

Celtina nodded her head in agreement. “Only the links of the chain are made of words, leading from Ogmios’ tongue to Garanos’ ear.”

They both stared in amazement at the astonishing sight until Ogmios stopped in front of them.

Bretanos was at a loss of words for a moment. “How is this possible?” he finally asked. “You have no weapons. Unless your walking stick is really some sort of mighty club.”

Ogmios ignored the jest, turning instead towards Garanos. “Tell Bretanos what we talked about.”

Garanos cleared his throat. “I didn’t realize the importance of the cattle and how taking them could affect the survival of your people. In recompense for my actions, I offer my services to you and your people.” Ogmios nudged Garanos with his walking stick. “Oh, yes,” Garanos continued as if he had just remembered a missing portion of a predetermined speech. “I offer my services for the time period of three years.”

Bretanos was stunned. He didn’t know which was more amazing: that the old man had been successful or that Garanos was making this proposal in recompense.

“I accept your services,” he finally answered.

Garanos glanced towards Ogmios as if he was unsure of what to do.

“Go,” Ogmios told him, “and introduce yourself to the people so that they will not be afraid of you for the next three years.”

Garanos nodded his head in agreement and then made his way towards the crowd of onlookers.

“Let us go inside,” Bretanos said to Ogmios. “Surely you need to sit down and rest after such a long journey.”

“I thank you for your kind hospitality,” Ogmios replied.

Once he was refreshed and had drank a cup of wine, Ogmios addressed the chieftain. “It is true that I have no standard weapons. No sword or spear, or even a club as you jokingly referred to my walking stick.” Ogmios paused long enough to chuckle and then continued. “No, the most powerful weapons I possess are my words.”

“Your words?” Bretanos asked. “How are your words a weapon?”

Ogmios smiled. “Let’s just say that I know the right words to say and how to say them.”

“Now you’re talking in riddles,” Celtina said.

“Indeed, sometimes I do,” Ogmios answered with a laugh. Then his tone turned serious. “But then other times, I am straight to the point.” He turned his attention to Bretanos. “Like I am now. My reward for returning your stolen cattle to you?”

“You mean my daughter?” Bretanos hesitantly asked.

“You did offer her hand in marriage to the one who returned your stolen cattle.”

Bretanos shifted nervously in his seat, unsure of how to respond.

“The offer still stands,” Celtina said with conviction in her voice. “My father and I have already discussed it. Marriage with me will be your reward.”

“Not only are you a very beautiful woman,” Ogmios told her, “but I can tell you are also very strong and brave. Your words and actions today have shown me those things.” Ogmios slowly stood up. “However, I will take only that which is freely given to me.”

As he made his way towards the door, Celtina called after him, “You are speaking in riddles again!”

Ogmios stopped and turned around. “Am I? Or am I being straight to the point?”

Celtina was silent as she studied the old man in front of her.

“At least let us give a feast in your honor tonight,” Bretanos said before Ogmios could leave.

“I do enjoy a good meal,” Ogmios said and then left.

But although he was gone, Celtina’s mind still lingered with thoughts of Ogmios.

That night, Bretanos gave a splendid feast to celebrate the deed of Ogmios. They held the feast outside because all of the people attended. The main course consisted of a huge pig slowly roasted over a pit, from which Ogmios chose the Champion’s Portion, the choicest cut of meat.

As they ate and drank, the feaster’s attention was focused on Ogmios as he recounted for them how he took back the stolen cattle from Garanos.

Celtina paid attention to Ogmios as well, but not to his story. She had already heard that earlier. No, she focused on how Ogmios now appeared to her.

There was no denying how old he was and, if she had to be honest with herself, the thought of marrying him had repulsed her even though she would never break her word to marry whoever had won back the cattle.

But now when she looked at him, his age didn’t matter. And it wasn’t because he had accomplished what the young warriors of the tribe were too afraid to even attempt or even that he had done it with his words rather than a sword, an incredible feat that she still found amazing.

No, it was because of what he had said about her. She supposed she was beautiful because she had heard it told to her so many times especially by her suitors. But Ogmios had also praised her for her strength and bravery, qualities which she was more proud of than her beauty. Her beauty would fade and one day she would be just as old as Ogmios. But she would carry her strength and bravery with her all of her life.

That was the reason why she looked upon Ogmios differently now. And also because he could have demanded her hand in marriage as the promised reward, but he would rather have Celtina choose to marry him rather than marry him under some obligation. His words to her which had at first seemed so cryptic were now perfectly clear.

Celtina’s thoughts were interrupted by her father. “I’m sorry,” she said, clearing her mind of Ogmios. “What did you say, father?”

“I asked if you were alright,” Bretanos asked again. “You have been quiet all night and seem like something is troubling you.”

“No, nothing is bothering me,” she answered. “Just seeing things in a different light.”

Before her father could ask what she meant, she stood up and excused herself. After retrieving a drinking bowl, Celtina walked over to the stream not too far away from where the feast was being held. When she reached the stream, she dipped the drinking bowl in and retrieved some of the water, remembering to say a few words of gratitude to the stream for her gift.

As she made her way back to the feast, Celtina felt like all eyes were watching her although the feasters were more involved in their own conversations. She entered the middle of the feasting circle and then stopped. She faced towards Ogmios, waiting for the conversations around her to die down.

Finally, after everyone was silent, Celtina walked towards Ogmios. When she reached him, she knelt down beside him and held out the drinking bowl towards him.

“I offer myself freely to you,” she said.

Ogmios took the bowl and drank from it. He then offered it back to Celtina. “And I offer myself freely to you.”

Celtina retrieved the bowl and drank from it as well.

And with that simple gesture, Celtina and Ogmios were betrothed.

That night, Celtina took Ogmios to her lodging. Within a month, she knew that she was with child. Though Ogmios was happy they were going to have a child, Celtina also noticed that he acted sad. And the sadness seemed to grow with each passing day.

Although she had a feeling of impending doom, Celtina never brought it up with Ogmios and didn’t ask what was weighing on his mind.

“His name shall be Galatos,” Ogmios told her.

“Galatos,” Celtina repeated as she pulled the baby closer to her chest. “What does it mean?” she asked, glancing up at Ogmios.

“It means ‘Valorous One’. He will face many dangers in his life.” Ogmios smiled at Celtina. “But luckily, he has such a brave mother, who can not only pass on that quality to him but can teach him to be brave as well.”

And then Celtina understood what had been bothering Ogmios all these months. “You’re leaving, aren’t you?”

For the first time, Ogmios was at a loss for words and didn’t know what to say. He had known this day would come and had been dreading it. But he had to leave and there was no way he could stay.

Ogmios nodded his head. “The obligations that I have with my own tribe have been neglected for too long. No matter how much I want to stay, I must return.”

Celtina didn’t completely understand, but she could understand the sense of honor and duty that Ogmios was feeling. “What about Galatos? One day, he may have a need for his father.”

“I will always be with Galatos and keep a watchful eye on him.” He held up his walking stick, closed his eyes, and whispered some words that Celtina didn’t understand. When he was done, he went to a corner of the room and leaned it against the wall.

He turned back around to face Celtina. “When he is old enough to lift that, then he will be ready to walk forward and face his destiny.”

Celtina looked down at Galatos, rocking him and smiling. When she looked back up, Ogmios was gone.

Thanks to the Bardos/Brennos of Galatîs Litauiâs Cunolugus Drugaisos for providing his words for us in the creation of this.