Among modern Celtic-inspired traditions, Samhain is often seen as the “Celtic New Year,” a festival marking the descent into winter. However, a close reading of the ancient Coligny Calendar it reveals a fundamental contradiction to this popular interpretation. The Gaulish year does not begin in darkness but with Samonios, a month whose name and timing signal warmth, light, and the primacy of vitality at the year’s outset. This challenges widespread views and reframes our understanding of the Gaulish annual cycle.

This observation raises a deeper question, both linguistic and spiritual: how did a word originally associated with summer come to be associated with the beginning of winter?

The Etymology of Samonios

The name Samonios (samon-) is linguistically connected to the Proto-Celtic root samo-, meaning “summer.” Cognates appear across the Celtic languages. Old Irish sam, Welsh haf, Breton heven, and Gaulish samonios all refer to summer or the warm season. This suggests that Samonios was originally the summer month—a fitting beginning for the bright half of the year (Samos). Much of the confusion about its meaning comes from later Irish parallels, particularly Samhain, which marks the descent into Giamos (darkness, winter). Some scholars have suggested that Samonios may mean “end of summer” or even “assembly,” viewing the word from a ritual or social perspective rather than a seasonal one.

To further probe this question, consider that the better key to understanding Samonios lies not in its own ambiguity — but in its counterpart, Giamonios.

It’s hard to say what many Coligny months mean. Most interpretations hinge on Samonios—“summer,” “end of summer,” or “gathering.” Instead, we should start with the less disputed Giamonios. The root giam links directly to Proto-Celtic gīamos, meaning “winter” or “cold.” No one claims Giamonios means “winter’s end.” It clearly denotes the dark, cold season. This would be a poor choice for a summer month. This strongly implies Samonios and Giamonios are true opposites, structuring the calendar with a dual rhythm of light and dark.

Further evidence lies in the infix –on–, common in Gaulish divine and cosmic names (Tarvos Trigaranos, Maponos, Epona). It is often taken to mean “great” or “divine.” Thus, Samonios may carry the sense of “Great Summer” or “Divine Brightness.” Giamonios could mean “Great Winter.” They stand for the two vast halves of the sacred year.

Therefore, the Coligny Calendar begins in the season of light—Samonios. This directly refutes the widespread idea that the Celtic year starts in darkness. Instead, it demonstrates that, contrary to common belief, the ancient Gaulish year starts with vitality rather than decline. The Gauls seemed to have deliberately placed cosmic order at the heart of their calendrical beginning. This choice is mirrored in the Greek Attic calendar and is central to the Gaulish worldview.

From Samonios to Samhain: The Semantic Drift

As Celtic languages and cosmologies evolved, Samonios shifted in meaning toward the winter season. Its descendant, Old Irish Samain (later Samhain), was placed not at the start of summer but at winter’s threshold. This shift illustrates how a word tied to summer was semantically repurposed to signal the onset of winter as the Goidelic world redefined the year’s turning points.

Part of this transformation can be traced to Christianization. As Christianity spread across the Celtic-speaking regions, older seasonal festivals were recontextualized within the Christian liturgical year. The establishment of All Saints’ Day on November 1st directly overlapped with Samhain, strengthening the association of the festival with the descent into winter and with the veneration of the dead. This overlap reoriented both internal and cultural calendars, integrating older seasonal observances into the rhythm of Christian feast days.

Early Irish sources mirror this shift. The Sanas Cormaic lists Gaimain after Samain, fixing Samain in late autumn. Martyrologies like the Félire Óengusso and Annála Connacht also link Samain to winter, cold, darkness, and the beginning of the year’s waning half, in step with All Saints’ Day.

Brythonic languages kept the original meaning: Welsh haf and Breton hañv still mean “summer.” In Gaulish and Brythonic contexts, Samonios’ summer association persisted even as Goidelic traditions reinterpreted it for winter.

Samhain thus marks a deeper transformation than a mere linguistic shift. It embodies a process of semantic drift—where words change meaning over time—reflected in the shift from naming the ‘month of summer’ (Samonios) to marking the onset of winter (Samhain). This drift happened gradually as changing cultural, religious, and social realities redefined the word’s role. Shaped by evolving cosmologies, regional distinctions, and the Christian reinterpretation of indigenous seasonal markers, the term that originally meant the entrance into summer eventually came to signify the beginning of winter. This shift demonstrates how a festival rooted in summer evolved, through reinterpretation, to signal the arrival of winter.

Time, Decolonization, and the Gaulish Perspective

For many who engage with Bessus Nouiogalation (BNG), the most significant distinction is that the year begins in spring or early summer rather than in fall or winter. This fundamental shift alters our cosmological orientation. While the ancient Gauls—our ancestors—held diverse perspectives and were not bound by identical rituals, BNG is rooted in intentionally moving away from Western seasonal and religious frameworks, which typically start with decline rather than growth.

Decolonizing practice is not just rejection—it is reorientation. It means reclaiming the Gaulish view of time: not linear from birth to death, but circular, with light and dark generating one another.

Yet why did the Gauls begin the year in the bright season, when their mythology often highlights night, Antumnos (the Otherworld), and the depths of Dubnos (The lower world)? They started days at nightfall and believed themselves born from the Otherworld—ideas seemingly more in line with winter.

Perhaps because light is born from darkness, to begin the year in light-honored creation. As dawn follows night, Samos rises from Giamos. Seeds buried in the earth reach for light and warmth. The Gaulish year, split into two halves, joins rather than opposes them. The 19-year Metonic cycle reinforces this: time is a great spiral, always returning yet never the same.

Starting the year in Samos was not a denial of darkness—it affirmed that we carry light within despite our origins. The Gaulish calendar encodes a cosmic renewal: birth follows death, and it is light that marks the beginning.

The Flow from Samos to Giamos

Understanding Samonios as the start of the bright half of the year centers BNG’s argument: the Gaulish worldview begins with presence, vitality, and cosmic order, not absence or dissolution. Giamos, associated with darkness and decline, follows Samos in a necessary cycle, but the year’s initial movement is toward light and creation. Stating this principle foregrounds the intended argument: choosing to start the year in light is a deliberate cosmological statement about beginnings.

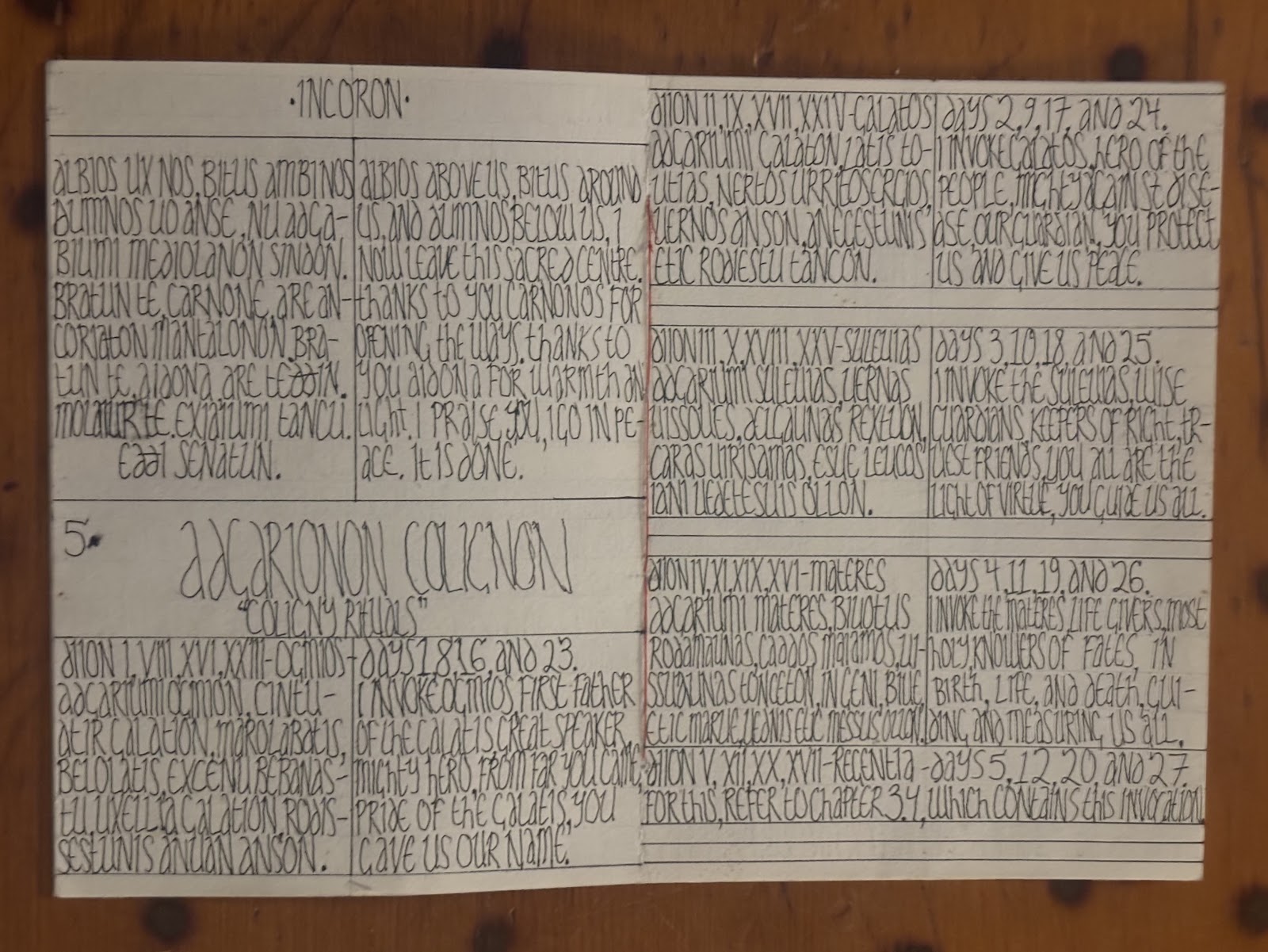

Reconsidering Trinux Samoni

It’s worth noting that many popular interpretations of the Coligny Calendar differ greatly from what the evidence suggests. As researcher Helen McKay aptly observes:

“Like the idea that Samhain starts the Celtic year – which it doesn’t, or that the Celts counted from the dark times of the day, month, and year – which they don’t, they only counted the day from sunset, just as most of their neighbours did, nothing more. Or that their lunar month started with the full moon, which it doesn’t. Or that the notation TRINUX SAMONI refers to three days of Samhain – which it doesn’t.”

— Helen McKay, “Where Does the Coligny Calendar Sit?”

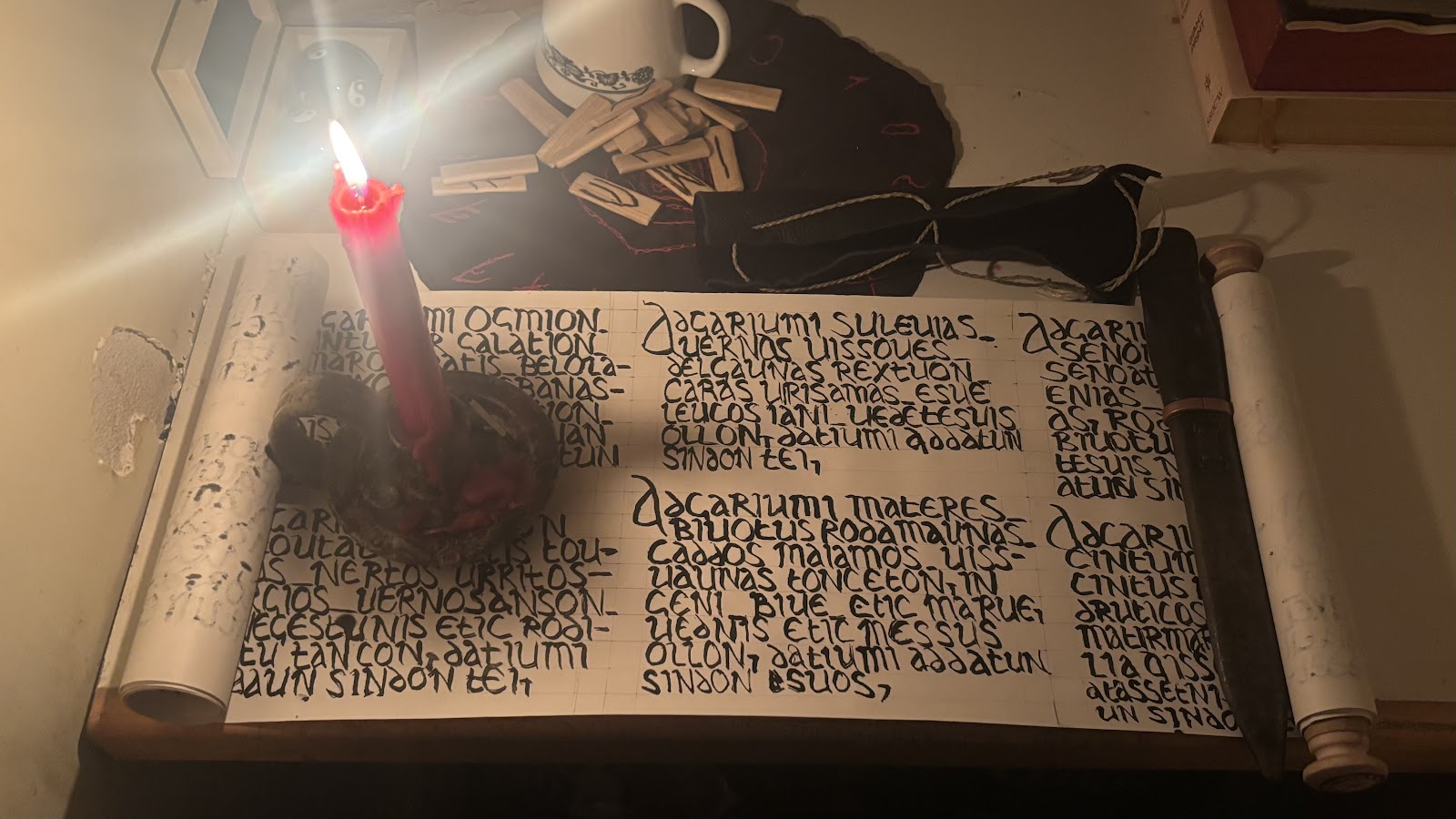

Trinux Samoni, literally meaning “the three nights of Samonios,” did not signify the start of winter, but instead marked a liminal transition tied to renewal—most likely situated at the boundary of Samos, the bright half of the year. BNG’s approach aligns with this interpretation. When the evidence is considered outside modern seasonal frameworks, it is apparent that the year’s cycle commences with illumination. This does not deny darkness, but acknowledges that light emerges from it; we are born from darkness. Thus, the so-called “three nights of Samonios” represent not an entry into winter but an emergence into renewed vitality—rekindling cosmic order after Giamos. Here, at the beginning of the year, vitality first arises. More details on that holiday here.

Cintugiamos: The Descent and the Ancestral Turning

Within the modern practice of Bessus Nouiogalation (BNG), we still recognize a sacred time for death, descent, and remembrance — a festival called Cintugiamos. Occurring toward the end of autumn and the beginning of winter, it parallels Samhain in function but retains a distinctly Gaulish cosmological frame.

During Cintugiamos, the light of Samos wanes, and the days turn inward toward Giamos — the descent into Dubnos, the deep realm beneath all things. It is a time to look to the Regentiâ — the Ancestors — for guidance, as the veil between the realms thins.

Alongside the honored dead, we turn also to the ancestors of our Bessus: to Ogmios, master of eloquence and the binding power of words, and to Celtînâ, the deep well of wisdom and inspiration. Cintugiamos shows us that as light fades, wisdom deepens — that the turning inward is not an ending, but a communion with the roots that nourish life’s return. You can read more about Cintugiamos here.

References

- Duval, P.-M. (1976). Les Celtes. Presses universitaires de France.

- Olmsted, G. S. (1992). The Gaulish Calendar: A Reconstruction from the Coligny Calendar.

- Lambert, P.-Y. (1994). La langue gauloise: Description linguistique, commentaire d’inscriptions choisies. Errance.

- Green, M. (1992). Dictionary of Celtic Myth and Legend. Thames & Hudson.